One reason organizations exist is to do things that would be hard for one person to do by themselves. For example, it's hard to conceive of one person building an office building. Instead, we have organizations of thousands of people with diverse skills that work together to build buildings. However, coordinating, controlling and just keeping track of a lot of individuals introduces its own problems.

One way to solve these problems is to create a hierarchical system of supervision, so that small groups of workers (up to say, 50 people) are supervised by coordinators (managers). Depending on how many people there are in the organization, the coordinators themselves need to be organized into groups supervised by higher level managers, and so on. Part and parcel of this hierarchical supervisory system is the cutting up of the organization into groups (departments).

The question arises: On what basis should we carve up the members of the organization into subunits? What would happen if we did it randomly, without regard for tasks? One problem would be that each manager would have to be aware of what needed to be done in every area of the organization, in order to direct his/her workers. This would be impossible in most cases.

What organizations actually do is group people in a way that relates to the task they perform. This still leaves a lot of possibilities. Here are six common bases for departmentation:

Actually, some of these (like #1-Knowledge and #2-Work Process) can be impossible to distinguish. In general, it is more useful to think in terms of two basic categories, which are generally called function and market, but which you might think of as Means and Ends. Here's how the seven categories above fall into the two supercategories, along with some other information about the two categories:

| Means (Function) | Ends (Market) | |

| Specific Types |

|

|

| Kinds of Companies |

|

|

| Strengths |

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

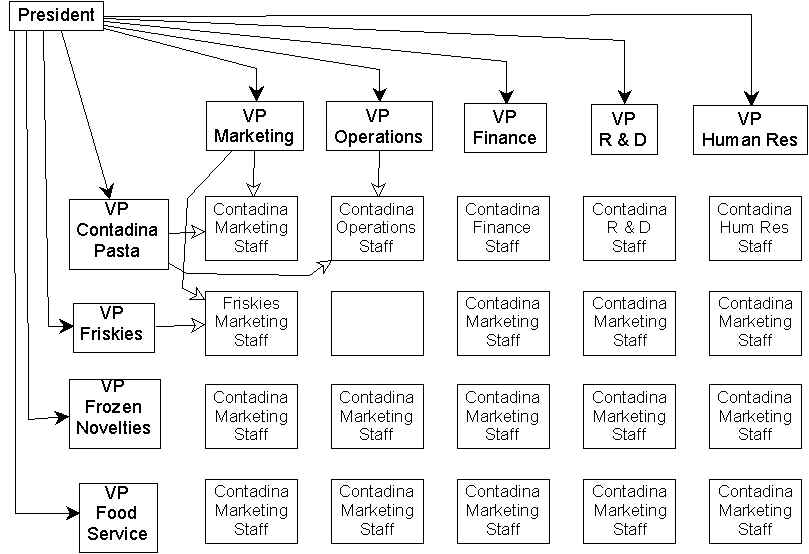

An attempt to organize company according to both function and market dimensions simultaneously, so that each person belongs to both a functional department and a product/market department. Some people therefore report to two bosses.

The big advantage of matrix organizations is that they are great for sharing of information and enabling people to coordinate their efforts with larger organizational goals and strategies.

The problem, of course, is that having two bosses can be confusing, and is a situation that is easily exploited by subordinates, who can pit their bosses against each other. The subordinates can also be unwitting victims of power struggles among the bosses.

The matrix form works best when one dimension is a permanent affiliation (typically functional), and the other is a temporary dimension, such as a client project. So a person is, say, a marketing research analyst, and is presently assigned to the Carnation project, which will take 6 weeks, and will then be assigned to the R.J. Reynolds project, and so on.

An organization can divide itself into departments any way it wants using any criteria it wants -- there is no law about it. It doesn't have to be rational. However, there is a theory (developed by James Thompson) about what is the best way to do it. According to the theory, there are 4 basic rational criteria for choosing the bases for departmentation:

This refers to the flow of product from person to person as it is being constructed. There are four kinds of increasingly tight interdependence:

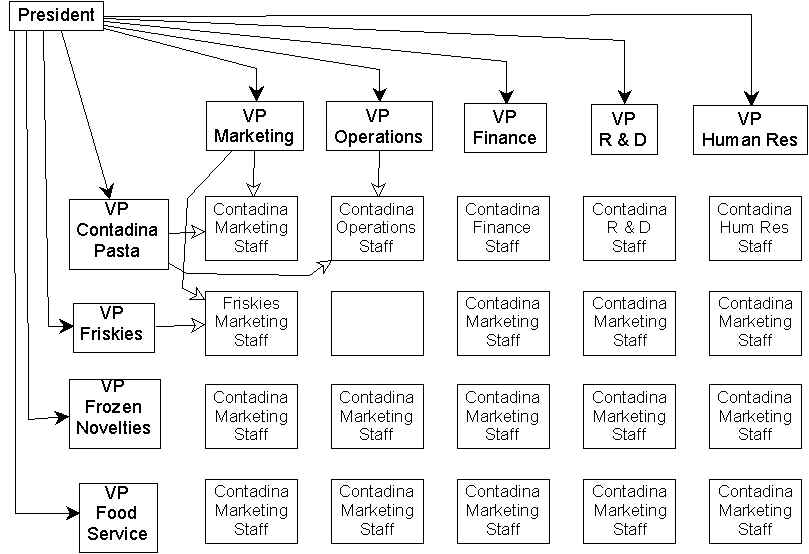

Now here is the key idea: where work-flow interdependence is critical, rational organizations try to group tasks/positions together which are more tightly interdependent. That is, operations which are team-interdependent should be grouped first (i.e., at the lowest levels in the organization), operations that are reciprocal-interdependent should be grouped second, and so on. This is illustrated in the figure below, which gives the organization chart of a hypothetical manufacturing organization.

Counting from the bottom up, the first and second groupings are by work process, the third is by business function, and the fourth is by output (product). Now think about it in terms of interdependencies. The tightest interdependencies are between the turning, milling and drilling operations. These are team or reciprocal interdependencies. So they are the first to be grouped together (under "General Foreman: Fabricating").

The next tightest interdependencies are the sequential interdependencies between fabrication and assembly, since first you make the materials, then you assemble them. So these are grouped together under "Manager: Manufacturing".

There are also sequential interdependencies between the business functions of design (engineering), manufacturing, and marketing. So at the next level up, we merge all of these under "Vice-President: Snowblowers".

Above this level, most of the workflow interdependencies are only of the pooled variety: the snowblower department really has little to do with the frostbite remedy department, except that they all dip into the same general pool of organizational resources (capital, management talent, physical assets, etc.).

This refers to consultations among people about how to do things. For example, lawyers in a corporation consult each other to take advantage of specialized skills and to develop a common approach to things.

Groups formed in order to achieve economies of scale. For example, if each department in a factory has a maintenance person, it may be inefficient because the small departments don't have quite enough work for a fulltime maintenance person, while the big departments have too much.

This approach also encourages specialization, as within a central maintenance department there can be specialists for different kinds of problems.

Groups are formed in order to minister to people's social needs. This often leads to functional groupings because people are comfortable with their "own kind" (as in technical people prefer technical people, sales types like sales types, etc.).

Often there are individual concerns, like two people who don't get along, the force certain departments to be placed under other departments, or not placed under certain departments.

| Copyright ©1996 Stephen P. Borgatti | Revised: January 17, 2001 | Go to Home page |